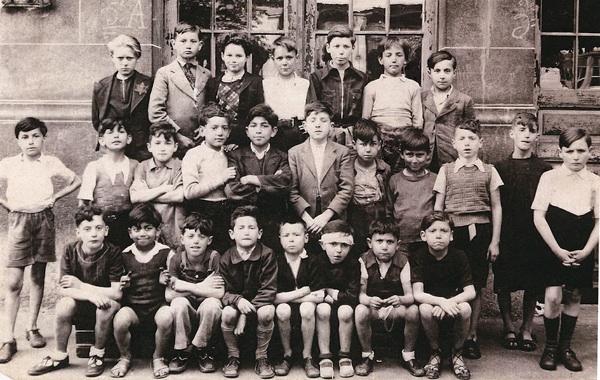

Schoolboys in Paris 1942-one is wearing a yellow star (top left)

Letter from Paris – August 2012

Among the thousands of chansons about Paris there is one cheerful popular song by Yves Montand about the Vélodrome d’Hiver, the covered cycle track which used to be in the 15th arrondissement, not far from the Eiffel Tower. A few years later this uncomplicated celebration of working-class leisure (the Popular Front government had recently established paid holidays) was overshadowed by what the French historian and member of the Resistance, Marc Bloch, dubbed the “strange defeat” of May 1940.

German propaganda accounted for the ignominious capitulation of the French Army by mocking its heterogeneous nature (there was footage of men from African colonies contrasted with the “civilized” and disciplined German troops) and the lack of patriotism of the people in general, as they fled in panic – a charge particularly laid at the door of Jewish citizens as well as more recent immigrants from Nazi and Russian persecution. Unfortunately, such attitudes found an echo in the French Right Wing. When the Vichy government, under Marshal Pétain (who had served honourably in the First World War) signed an armistice in June 1940 there were many who took advantage of the situation to settle scores. The issue of collaboration remains a very sensitive one to this day.

The Dreyfus affair at the turn of the century revealed an anti-Semitism that extended into many areas of French society and culture, and some of its vocabulary is still relevant today. For example, when a journalist who had investigated the questionable activities of Bernard Kouchner (well-known as the “French Doctor”) characterised him as “cosmopolitan”, Kouchner was able to argue that the journalist was motivated by anti-Semitism. Ever since the Dreyfus affair, and especially during the occupation, Jews were described as “cosmopolitan” – that is that they were not really French, had no roots, formed part of a shadowy international movement…(Ironically, analogous arguments are now applied to those of North African origin, even though some of them are second or even third generation immigrants). Be that as it may, events of 70 years ago still have a real presence in contemporary France.

An illustration of this brings me back to the Vel d’Hiv, as the 1930’s cycle track figuring in Montand’s song was known, for it has given the name to the most notorious round-ups of French Jews. One of the first ordinances of the occupying forces was to oblige all Jews to register with the police (irrespective of whether or not they were French citizens) and by spring of 1941 there were already mass arrests of Jewish men, who were taken to internment camps (the most notorious in Drancy, just outside Paris) from whence they were transported to concentration camps. A number of other measures followed, obliging Jews (including children) to wear a yellow star, forbidding them access to various professions, and even excluding them from public places such as gardens and parks.

The evidence suggests that French citizens were mostly indifferent to all this (there was little of the militant anti-Semitism of Germany and East European countries) and some of the more blatant propaganda in cinemas was not well received. Mendès-France, who spent much of his time hiding in cinemas when he was on the run, mentions this in the documentary Le Chagrin et la Pitié – a film which gives a fascinating view of life during the dark years of the occupation.

The Vel d’Hiv round-up was a turning point in that it was meticulously organized on a large scale (some 9000 French police and gendarmes took part). In two days, the 16th and 17th July 1942, over 13,000 Jews including 4,000 children were rounded up and herded into the stadium, in appalling conditions. They were subsequently taken to Drancy and on to concentration camps from which only a handful returned.

A small footnote to underline the contemporary relevance of these events: successive French presidents refused to acknowledge the role of the French in these terrible events. For De Gaulle the real France was not Vichy, but the Resistance, and all subsequent presidents were in agreement with this, until 1995 when Chirac apologized for the complicity of the French state in what he called “criminal madness”. Sarkozy was reluctant to express collective responsibility (although he did propose a law making holocaust denial an offence – a law which was extended to include the Armenian genocide, much to the chagrin of the Turkish government). The issue came alive again after the new president Hollande gave a speech in which he said that the roundups constituted a crime in France by France. Several conservative politicians (and some on the left, too) have vigorously condemned his speech, some in very strong terms. This issue still resonates today.

Finally, I would like to recommend some films (apart from the documentary I have already mentioned): M. Klein, directed by Joseph Losey, and Au Revoir Les Enfants, directed by Louis Malle, together with the latter’s chilling Lacombe Lucien, which examines the subject of collaboration. Conditions in the Vel d’Hiv are vividly recreated in the film Sarah’s Key, based on a book of the same title.

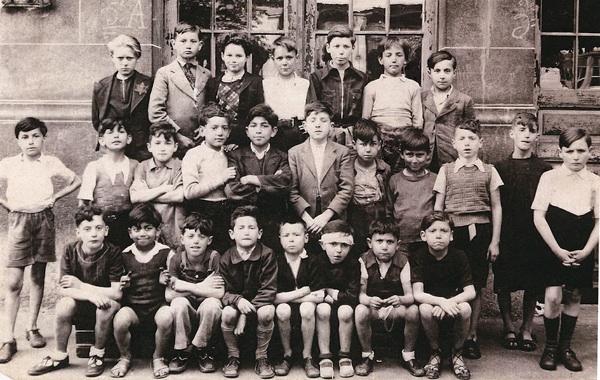

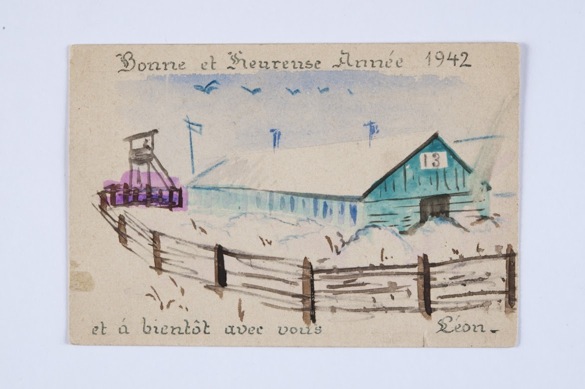

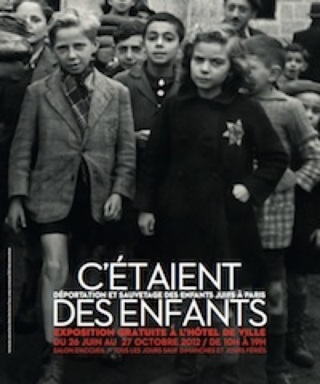

PS As part of the commemoration of the 70th anniversary of this event, the Mairie de Paris organized an exhibition in August 2012 which concentrated especially on the deportation of Jewish children, but also on the various resistance and help offered by French citizens (officially recognized by Israel as “les Justes de France”) who in various ways, at the risk of their own lives, saved thousands of Jewish men, women and children. It was a sober and moving exhibition, with letters, drawings and some photos (most of which were specially taken by the Germans to give a positive impression of the conditions). The exhibition continued until the end of October.