Letter from New York January 2011

Another blizzard visited during the night. It is early morning, and I am in the silence of snow. Nothing is moving. Stung by criticism that New York was paralyzed by a blizzard that hit a few weeks ago, Mayor Bloomberg took no chances. A weather emergency was declared hours before the snow was predicted to fall. A command center was set up. Plows stood at the ready. But weather being the unpredictable thing it is, it was the northern suburbs that were buried. I am looking out the window at snow-covered pine trees and my buried car. Soon there will be the scrape of shovels and the shouts of children home from school. For now, all is still. I look out at dark limbs weighed down in white against blue dawn and remember other snows.

I remember that one winter in my home town in Northern New York, the snow drifts were so high we could step up onto our porch roof. Taking sleds off porch roofs was common that winter. The snow became so deep that U.S. army tanks from nearby Fort Drum were dispatched to help clear the streets. “This may be what it’s like to live in Siberia,” said my mother, who grew up out west and saw much snow but nothing that required heavy artillery.

Seeing the world covered in snow instilled a sense of the vastness of life in me—and also a sense of intimacy. I would marvel at how beautiful it was, especially at night under the stars. The cold would inspire me to remember that I was standing on a planet orbiting through space, our solar system but a tiny part of a vast universe, and that would really make me shiver. Fresh deep snow has a cold stone smell and the acoustics of a great cathedral. Even soft sounds carry a long way, and everything seems closer. I would feel close to our early human ancestors. They must have been constantly aware of mortality, I realized, and the way conditions always keep changing, one thing flowing into the next. James Joyce called the impermanence of life and the certainty of death the “grave and constant” in human suffering.

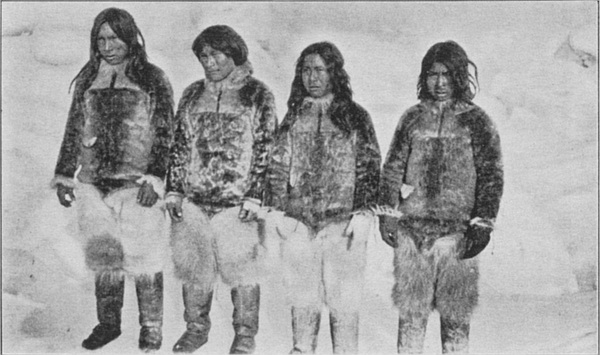

Our ancestors learned this in the Cathedral of Nature. Igjugarjuk, a shaman of a Caribou Eskimo tribe in northern Canada once told European visitors that the only true wisdom “’lives far from mankind, out in the great loneliness, and can be reached only through suffering. Privation and suffering alone open the mind to all that is hidden to others.’”

Snow or no snow, I think most children intuit that a greater awareness—a greater way of being—is possible, that it comes out in us when we confront great essential forces. I used to sense this. I believed I was secretly capable of knowing the kinds of things that Igjugarjuk knew, that our earliest ancestors knew. Into adolescence, I believed that if I was put into the right conditions and given the right kind of mentor and training, I might secretly be capable of greatness.

My father’s ancestors were Scottish, English, and Dutch, hardy people, farmers and captains of ships that sailed the St. Lawrence River. My mother’s parents were from Denmark, and the ancestors I thought most about were the Vikings- big and blond and wild. I skipped over the Viking reputation for pillaging and focused on fierce warriors like Beowulf, men (and I added women) who faced down terrifying monsters like Grendal, who crossed icy seas in open boats, who told inspiring sagas in the Mead Hall.

My mother grew up in the Great Plains of Western Nebraska, and I often visited there. I was awed by the vastness of the plains, and by the Plains Indians I saw perform ceremonies in war dress, the Blackfoot, Cheyenne, and Lakota Sioux. In my child’s mind, I made no distinction between the Plains Indians and the Vikings of my imagination. They were similarly fierce and brave and capable of deep knowing. They had minds that included the body, that were true to their essence, wild minds that were not separate from nature and the cosmos and what is hidden to others. When I grew a little older and discovered Herman Hesse’s “Siddharta”, I began linking Vikings and Sioux with Indians from ancient India. When I took a course in Indian religion and learned of a pre-historic Aryan migration in which a mysterious people swept down into India from the north, I pictured big blond Vikings on horseback riding like brave Lakota warriors into Mother India where they dismounted and perfected yoga and meditation. I pictured them sitting with legs crossed under trees, channelling all that fierce warrior energy into concentration and awareness.

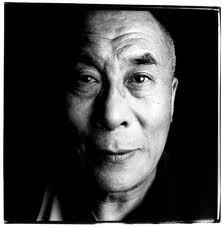

Somewhere along the way, I learned that “veda” means knowing with heart and mind together. I pictured the Rig Veda, the oldest of all known books refining all that fierce attention into penetrating insights about the laws that govern life, into a wisdom that is not separate from love and compassion, from an awareness of our inextricable connection to the Whole. Out of college, I read about mysterious people in Central Asia, in Tibet and Mongolia, who understood what it means to be awake. I visited a famous archeological dig site in Agate, Nebraska. There I saw photos of Plains Indian chiefs and was astonished to see how much they resembled the Dalai Lama. Their noble posture and fierce gaze was the same. Tibetans and Mongolians became part of my tribe.

Years later I sent a scraping of cells from inside my cheek to the National Geographic “Genographic Project.” This genetic population study is attempting to chart the migrations of earliest humanity based on the marking that sometimes get notched onto our DNA as it gets copied and passed down through generations. How astonishing it was to receive a world map of my matrilineal DNA and see a red line that begins in East Africa and a human being who lived about 150,000 years ago, our common genetic Eve. Incomplete and flawed as this study may be, it is still rich evidence that each one of us–everyone everywhere, in every possible condition of life–is related. Why, ordinarily, do we have such a sense of separation from one another?.

That National Geographic map contained another surprise. It turned out that my grandmother, who was born and brought up in Denmark, had DNA that carried a rare “X” marker found in only two percent of the European population–but in many more Lakota Sioux, Ojibwa, Navajo and other indigenous North Americans. This seemed to be tantalizing proof that my wild imaginings were carried in my very cells. The red line in my map left Africa for Central Asia, crossed Siberia, the Bering Strait, the Great Plains and…trailed off. The notes included with my map said my “X” type was controversial. Much was still unknown. For example, how the “X” marker turned up in Denmark. I had my theory. I pictured fierce Lakota warriors sailing across the storm-tossed Atlantic waters in open boats, teaching prehistoric Vikings how to build great long ships and sail back to North America. I proudly told friends that I may actually be a missing link in our common understanding of the evolution of our humanity! The day after my mother died, I dreamed of a Viking funeral. I watched a ship containing her body glide out into still water at sunset as I stood on the shore. Is there something in us that comes from the deep past, from those who have crossed great waters? In cold weather, and whenever I have had to weather adversity and fear, when I have had to face the unknown, I pictured my mother and my grandmother and a long line of human beings stretching back to the dawn of humanity. I remember there are many people who have been brave and found ways to keep the fires lit, no matter what the conditions.

Sometimes I think of the few among them who came to know even more. I think of those who painted the Paleolithic paintings, those seemed to know and express our connectedness with life and with something Greater that dwells within and animates life. I’ve wondered if that was implanted in me also. By now, I realize that I can’t discover this through my imagination alone. I know that clinging and attachment to any map is a way to miss the wild unknown of the present moment. The truth is a pathless land. More and more, I think of human beings in circles rather than lines. When I sit or walk or pray, I feel the presence of those who have come before.

Tracy Cochran