The Origins of Designs found on Carpets and Textiles

One of the questions most frequently asked by new purchasers of Oriental carpets, rugs or textiles is ‘What does that symbol mean?’ The dealer, usually knowing little more than his customer will either shrug his shoulders or launch into some great fantasy of his own making. However due to careful and diligent research by a number of dedicated collectors and dealers, a clearer picture is starting to emerge. I realise that this is dangerous ground as no final conclusion can be drawn about the objective meaning of any design, and the unknown weaver who places it in a carpet may or may not know the symbolic meaning of particular design elements.

It is now established through archaeological finds and historical accounts that carpets and other weavings have been made for at least 2,500 years, and probably longer. Through research done on finds as far apart as Western China and the islands of the Mediterranean, a new type of dating is emerging from what are now known to be loom weights. This indicates how widespread and sophisticated ancient weaving was. Fragments of textiles and a carpet found in excavations made in the Taklimakan Desert show similar design features to weaving that is still being produced. This may be due to the nature of a particular weaving technique or to the human desire to copy but is probably a mixture of both. The ancient tabby-weave carpet found during these excavations which had been used as a shroud, shows design elements that are instantly recognizable to collectors of antique rugs. It has the same ‘running dog’ border that is found on many Yomut Chuvals and is known by their weavers as ‘married women’s fingers’. It also has other design elements that are found on Turkish, Caucasian and Chinese carpets.

Many of the names assigned to individual carpet designs were given to them by European or US dealers. ‘Running dog’ was the name given to a hooked border and ‘elephant foot’ was the name given to a gul, which really means rose and is deeply symbolic and ancient . Hadklu or Hatchli, which is Armenian for cross was used to explain the cross like design of Turkmen Engsi.

Some design meanings are clear. The garden designs found on Qashqai and other South West Persian tribal rugs represent a lush Paradise full of birds, plants and water- an understandable dream if you live in a hostile desert, having been moved there from the fertile valleys of the lower Caucasus. Gardens in some stylistic form or other are also represented in rugs and carpets from most weaving areas. Other design groups such as wedding processions can be seen woven into artefacts used as part of the ceremony.

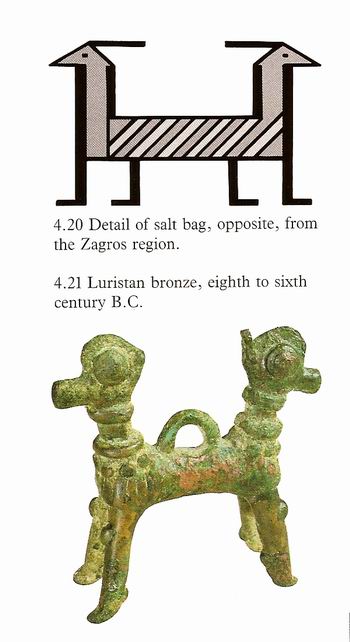

A breakthrough in understanding the origins of carpet design motifs came initially from the work done by James Opie, published in Hali as ‘Tribal Rugs’ in 1992. In the chapter, The Roots of Nomadic Art, he clearly explains how for example, zoomorphic Luristan, and Bronze Age Anatolian figures can also be seen in the designs on carpets. The most striking example is a double-headed horse figure, from the first millennium B.C. that is widely used on many Middle and South West Persian weavings

The use of birds’ heads with a long plumed feathers, lions, peacocks, dragons and of course the ‘tree of life’ can be found in the decorative art of many cultures as far apart as Scandinavia and Eastern China. Other widely used motifs that have developed from animal head designs can be clearly distinguished in a variety of carpet and other weavings. The root of the beliefs from which these designs spring can only be guessed.

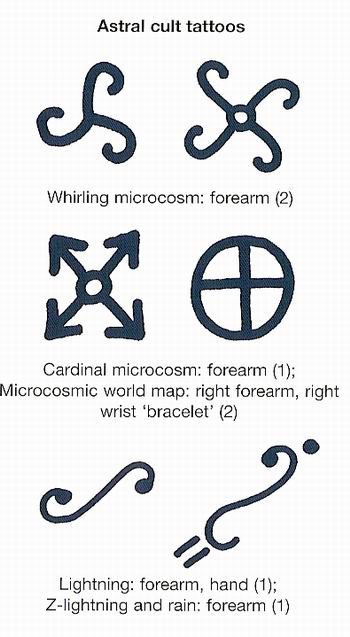

Earlier this year the book ‘Tattooed Mountain Women and Spoon Boxes of Daghestan’ was published (and has also been reviewed on this site). Designs seen on the bodies of old women and wooden and stone artefacts are widely used as motifs on Kaitags and rugs. So it appears that, at least within the Greater Caucasus mountain range, the symbolism used in textiles and carpets reflects a system of beliefs that runs deeper and is more ancient than any nominal faith a people might hold (if this seems far-fetched one only has to look at rural Ireland where an instilled belief in an older system of magic exists although nominally people may be devout Catholics).

In conclusion, to understand a symbol or design that has always fascinated you in a rug or textile, you need to look beyond the environmental conditions in which people lived when the piece was made, and try to penetrate the deeper historical, social, and religious context – although you may still be left wondering what the real meaning is!

Edward Stott