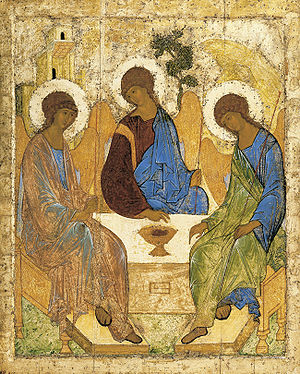

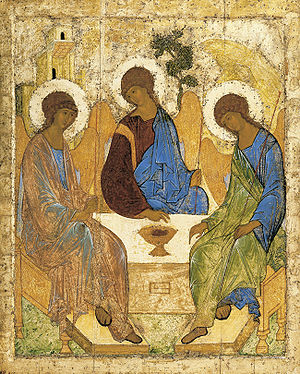

It may seem rather presumptious to write about an object which I’ve never seen “in the flesh”. However, since seeing a reproduction of this extraordinary icon in Richard Temple’s book, Icons – Divine Beauty (1), and having read Ann Persson’s little book entitled The Circle of Love (2) which gives some useful background, there has been a compelling wish to return and understand what is being represented.

The icon was commissioned by Abbot Nikon for the first stone church built in remembrance of St.Sergius of Radonezh, the founder of the monastery at Sergiev Posad, long regarded as one of the main centres of Russian Orthodox Christianity. St.Sergius placed the contemplation of the Holy Trinity at the centre of his teaching. It was painted by one of the most celebrated icon painters of the period, Andrei Rublev and was completed in 1427. The icon remained in situ within the church for over 500 years (as part of the iconostasis or screen dividing the sanctuary from the rest of the church) until 1929 when it was restored and moved to the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

There are two particularly arresting aspects of the painting which immediately distinguish it from most other icons from that time. Firstly, there is no obvious single central figure, and secondly the colours used are softer and more natural in tone.

In spite of the icon having lost much of its colouration due to age, and being viewed out of its original context (it would originally have been accompanied by the sights and sounds of the Orthodox tradition), one is immediately called into question when looking at the image. The impersonal harmony and symmetry of the three interrelated figures with their shimmering, complementary colours (implying continuous movement), and their location in the foreground of the picture is a real shock, as if we the viewers are being confronted by a universal truth.

What do the three figures represent and what is the nature of this being called into question? Could they represent thought, feeling and instinct? When looking at this image, it reminds me to try to sense my state, which is usually dictated by a particular thought, or emotion or physical sensation. Is it possible for these functions in us to work more harmoniously, and at a deeper level? And what do the house with the open doors, the tree and the mountain in the background represent?

If we undertake a very demanding task above and beyond the normal day to day requirements of life (for example an arduous walk at the limits of our endurance), we all recognise the strong impetus that allows us to start such an activity in a positive way. We also recognise how as the task progresses we encounter an inner inertia, an unwillingness to continue, which has to be overcome by an extra effort. If this inertia is only as strong as the initial impulse to start, then the task will not be completed. What is this extra effort? Is it possible that a third element is required which can somehow reconcile these two opposing forces? What would it be mean to become aware of these forces in oneself? The three figures in the icon are arranged so as to leave a space at the table. Perhaps this space is an invitation for us.

Could it be that the purpose of all the greatest ancient art across different traditions is to awaken in us a search for a latent sense of wholeness?

Geoff Butts

-

Icons – Divine Beauty, by Richard Temple, ISBN 0 86356 566 2, 2004.

-

The Circle of Love, by Ann Persson, ISBN 978 1 84101 750 1, 2010.

-

Note, the actual size of the Holy Trinity icon is 55 by 44 inches, which is large compared to many medieval icons.

-

Melvyn Bragg hosted a programme on the Trinity from his series “In Our Time” on BBC Radio 4 last week, and this icon is mentioned. Here is the link: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03xgl3m