This is the liturgical feast that celebrates and seals the experience of Easter, establishing in a moment in time the foundation of the inner and outer community of the church. It is a tale that depicts the first encounter with the Holy Spirit after Christ’s Ascension. Here the Holy Spirit appears as a Person of the Trinity, bringing forth, to those who had been prepared to receive it, a new perception and understanding, individually and collectively.

Pentecost, meaning fifty, marks the fifty days from Passover and Easter. It is interwoven into the Judaic festival of Shavot or the festival of weeks which looks back to the handing down of the laws by Moses at Sinai. Shavot is a joyous celebration of the early summer harvest. Both festivals are symbols of new beginnings; the first fruits: first laws, the first fruits of Christ’s teachings.

The story of Pentecost begins at dawn in a crowded room, the doors to the outside world are locked. Those who have journeyed together, who have witnessed and received Christ’s teachings are gathered together to pray. They have passed through the shock of the crucifixion, of Christ walking among them risen from the dead, and finally his ascension. Christ has now withdrawn to the Father. Into this circle of intense wakefulness and prayer a new element, the Holy Spirit appears. It arrives carried by a wind which blows opens the doors, and descends as tongues of fire penetrating each of them. The mystery of Trinity is born. God is now threefold.

From the Acts of the Apostles 2:1-11

‘When Pentecost time came round, the apostles had all met in one room, when suddenly they heard what sounded like a powerful wind from heaven, the noise of which filled the entire house in which they were sitting; and something appeared to them that seemed like tongues of fire; these separated and came to rest on the head of each of them. They were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in foreign languages as the spirit had given them the gift of speech’.

Spirit translates from the Hebrew word Ruah, which means breath, air. The wind is God’s breath. The fire is the transforming energy of the Holy Spirit, that which cannot be quenched. Into the darkened room the spirit descends and blows the doors wide open to the outer world. It is a sudden and dynamic new relationship with God. The shock that was experienced individually became embedded in the community and instantly the apostles are able to speak in tongues – a new level of communication, a new language that gives witness to the teachings they have received.

A tale of initiation and transformation. From a group of believers they become a group who know, ‘knowing’ is deposited in them. It is therefore considered to be a festival of community, of brotherhood and sisterhood.

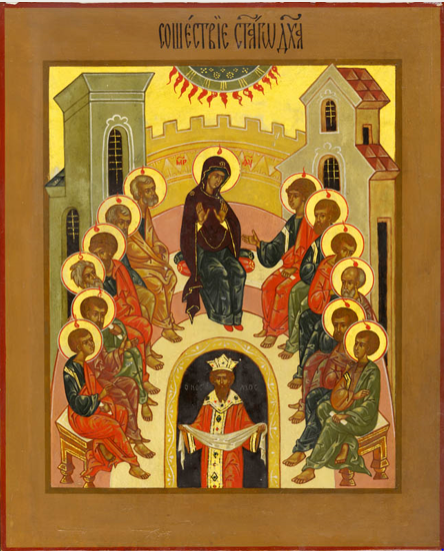

Mary’s presence within the group is represented in paintings and icons as the soul of the community. She personifies the Holy Spirit, having conceived of Christ through the spirit she is of the Spirit.

In the Orthodox tradition, (also witnessed in the Western monastic church) Rublev’s icon of the trinity is placed centrally for veneration and this is accompanied by the Pentecost icon depicting the tongues of fire hovering above the heads of the disciples and Mary who are sitting in unity around the King of the cosmos. The great Vespers of Pentecost include the prayers of Basil the Great, throughout which the congregation are invited to fully prostrate themselves. Pentecost Sunday is also

called Trinity Sunday, and in the Western church the Trinity is celebrated a week later.

The Pentecost story mystifies and perplexes, it expresses a truth at a level my rational mind cannot penetrate, speaking to an inner narrative that is usually hidden.

Marian Killick