Searching for the Source of a Tradition

It is strange that having had such a voracious appetite for exploring different kinds of music in my life, from the ‘progressive rock’ of the seventies to classical music, the blues, jazz, world music and free improvisation, a music so apparently simple and some might say innocuous as traditional Irish music should have stayed with me and grown in the way it has.

My first exposure to Irish music was probably listening to The Chieftains in the early seventies. Here, Paddy Moloney created a more ‘staged’ presentation of traditional tunes geared to both recording and performance in front of large audiences. Together with similar groups of the time they found a new audience amongst those seeking ‘authenticity’ in indigenous music. This was to a significant degree inspired by composer Sean O’Riada’s efforts to put the music (as with Eastern or Indian music) on a par with the western classical tradition. The following interview is of interest here https://youtu.be/bSn07vfWwKM, as is this documentary https://youtu.be/LJkWo0N3wbU. Later, the success of ‘Riverdance’ – a finely choreographed spectacle of Irish dance and music – was global. Today, the ‘Comhaltas’ network has achieved widespread success in organising the teaching of young people, and the ‘Irish session’ (an informal gathering of musicians, usually in a pub) has spread infectiously across the world.

I began playing the fiddle when I was about 24 years old, around the same time I first started listening to the Chieftains. This was rather fortuitous in some ways. On expressing a willingness to join Leicester Polytechnic Fine Art Department’s experimental ‘scratch orchestra’, the contemporary composer Gavin Bryars who was on the staff then, handed me a violin. How well you could play was relatively unimportant – ‘it was the spirit and the effort that counted’. But alongside playing pieces by Erik Satie I also started learning simple Irish and Scottish tunes. Given the inherent difficulties in learning the violin, my late start and that I was self taught, it has always been a struggle, yet these simple tunes have brought both joy and solace through thick and thin over the last 40 years.

Initially it was enough of a challenge to simply get the fingers in the right place and follow the basics of a tune. This stage lasted a long time, but looking back, it seems I have always been drawn to persisting doggedly with the seemingly impossible if something was of sufficient interest. Later, I came across a recording of the fiddler John Kelly. What struck me about his playing was the rawness of the sound, similar to the recordings of indigenous African or Middle Eastern music I’d listened to. These were expressions of musicians rooted in the everyday conditions of their lives and reflecting the wider influence of their environment and landscape. This fiddle music was unaccompanied, so one was aware of the solitary effort. In one sense it sounded primitive, as if played crudely, but one began to hear that it actually contained subtle complexities with its inflections, decorations, and interpretations. There was something about the rhythm in particular – when you tried it yourself you realised how elusive that ‘swing’ or ‘lilt’ was. Even after all these years, when I play, I can never take that for granted. It has to be found again and again, in the moment. Here is an example of John Kelly’s playing: https://youtu.be/G-7UpcbcQuM. The following documentary gives a good introduction to the music of County Clare and John Kelly can be seen playing with his sons 6min 20 secs in. https://youtu.be/rW8M6ZQdlYg.

This clip and similar documentaries remind us that in the early part of the twentieth century the music was usually passed on first-hand from one generation to another. The tunes, and the way they were played, were those known in that locality – those of the adjacent area beyond a good walk or a cycle ride away would be relatively unknown. Music would be played by just one or two musicians at the end of the working day within the home, sometimes in conjunction with a house dance. It is also suggested that the style of playing within a locality would have developed from the influence of a particular individual. Some tunes came from old songs telling of local custom, legend or courtship, usually in the Gaelic language. It is worth remembering that the history of the Irish people has been full of hardship and suffering as a result of oppression, famine, emigration or simply the challenges of day to day survival. The dance tunes kept the spirits alive, while the laments and slow airs gave expression to grief and melancholy. In the purest form of Irish singing, ‘Sean Nós’, the solo singer gives full reign to his or her powers of improvisation and embellishment in service of the song. Here is one example: https://youtu.be/V0SLZY2poY8. And here is a related documentary: https://youtu.be/GttbkOce0Ig.

Despite the life and spirit of the music, and the sheer beauty of some of its melodies, it struggled at times to survive the new forms of music and dance, emerging initially from America in the 1920s. Efforts by the government and the clergy to ‘contain’ the popularity of dance-halls led to the ‘regulation’ of music and dance. Smaller organised gatherings, including to some extent traditional house dances, were discouraged; dances became more formalised and the intimacy of the solo performance or duet was superseded by the ceili band. In one sense therefore the music increased in popularity, but this involved changes in context, content, scale and quality, fuelled largely by commercialism and the natural desire amongst the young to ‘move with the times’. My mother comes from County Cork and left Ireland when she was twelve ‘for a better life’ in England. She has always responded to my playing in a rather ambiguous way as if it was a harking back to times she had left behind. It is perhaps difficult to appreciate the changing sense of identity that has existed amongst the Irish during the first half of the twentieth century.

Being something of a loner I am used to quiet reflection and the creativity that can sometimes emerge from that, so I have always gravitated to playing the slow airs, or playing reels and jigs at a steady or even slow pace, so there is room for individual expression. ‘The Blackbird’ has always been a favourite tune of mine. It is a ‘set dance’ played at a lively speed but I have played it as a slow air for many years, even though I’d never heard anyone else playing it that way (the John Kelly version I’d heard earlier was quite a different melody). It was only recently that I discovered the seminal recording called ‘Star above the Garter’ by Julia Clifford and Denis Murphy, and was astonished not only at the number of slow airs (which are seldom played these days) but also that ‘The Blackbird’ itself was played as a slow air. I then discovered that these musicians came from an area called ‘Sliabh Luachra’ (the mountains of rushes), an area on the Kerry/Cork border, very close to where my mother came from in Dunmanway. It was one of those more desolate areas of poor soil quality that many retreated into to escape oppression in former times. Despite the hardship, traditional culture flourished in such areas. Sliabh Luachra is known for its poetry, its variety of musical forms (including slip jigs and slides), the steady pace and lilt of the music, and its slow airs. I felt for the first time that my gravitating toward this music was perhaps something coming from deep down in my bones and blood. Here is a clip of Julia Clifford playing a slow air followed by a more lively slide. It is astonishing to see such music coming from such a seemingly fragile frame: https://youtu.be/eWDzITNz7Tc.

Interestingly, it was in such areas that Sean O’Riada discovered the ‘real’ tradition of Irish music – he ultimately settled in the adjacent area of Muskerry. The music he heard would usually have been solo performances in intimate settings, in contrast to the ensemble performances he promoted, which carried a more grandiose, romantic and to some extent patriotic message, instantly appealing, yet at the same time ‘removed’ to a degree from its roots.

It seems clear to me that the potential for expressive depth within this music can only be realised if the physical aspects of playing can become responsive enough to serve the vision held in the mind. When the body is allowed to play its part in an alive yet relaxed way and the mind is sufficiently attentive, to the action and sound on the one hand, and ‘possibility’ on the other, then something new and unforeseen can take place. This is something very ‘quick’ which takes place in the moment. When one is closer to being ‘at one’ with the music, a faster tune is akin to an upland stream running downhill, like strands of ribbon, negotiating effortlessly the rocks in its path. There is I feel, something important here related to the idea of continuity. Each time one plays a tune there is the possibility of beginning from ‘zero’, a ‘not knowing’, which is an invitation to something more alive and unpredictable. One’s interpretation – the way it is played out – may involve hesitation, deviation, faltering and so on, yet strangely a sense of continuity can still be maintained, if they are embraced by something finer. This is very simple, yet at the same time very difficult – for me, for example, it is almost impossible to avoid a certain emotional intensity on the one hand, or fear of things falling apart on the other, which always threatens to get in the way.

Here is a clip of Paddy Cronin playing. He, along with Julia Clifford and Denis Murphy, was taught by Padraig O’Keefe, an important travelling fiddle teacher from Sliabh Luachra. These players acknowledged the importance of responding to the moment when playing. Cronin recalls O’Keefe remarking that ‘anyone who played a tune the same way twice was like a separator’. A separator was apparently a device which effectively took all the cream out of the milk! https://youtu.be/GX9LO114wm8. O’Riada at the end of the first clip mentioned above stresses the essential spontaneous nature of the music.

Today it could be said, from a certain perspective, that Irish music is thriving. There are many sessions in pubs, plenty of organised tuition (especially in Comhaltas), ceilidh bands, festivals and a proliferation of recording groups. On the other hand, some argue that playing has become more standardised, with less individual style and interpretation, and more focus on technique and speed. It is common today for instruments that are central to the music to be accompanied by keyboards or guitar which can bring about a significant shift in its feel. Solo performance has become something of a rarity. A solitary slow air may be included on a recording in a perfunctory way, and where songs are included for variety, they can often descend into something over sentimental or nostalgic. Often the emphasis can seem to be more on ‘the craic’ (entertainment value) rather than anything of a deeper level. There is a common assertion today that no one way (in any field) is ‘better’ than any other – they are simply different, but equal, on the same level so to speak, but is this to deny the importance of difference in quality (a vertical dimension)? Isn’t discernment an essential part of our innate (if sometimes hidden) human search for quality? The ‘pure drop’ as it is called, is still there to be found. Martin Hayes for example is renowned for the purity of his approach. In the notes for his and Dennis Cahill’s CD ‘Welcome Here Again’ he says:

‘There are as many ways to play Irish music as there are people to play it. One of its greatest strengths is in its flexibility of interpretation – everyone has the opportunity to put their personal stamp on it. We try to avoid an overly technical or cerebral approach. Instead, it is all about inhabiting the world of musical intangibles – the place that is governed by the heart, soul, feeling and instinct. The humility necessary to play this music meaningfully arises from a continuous struggle to enter that place.’

Here he begins with a slow air. It is worth listening to what he has to say after the first set of tunes: https://youtu.be/iubcj9YqyaA. Clearly Martin Hayes is playing the tune as he hears it, or rather, as it comes through to him – there is an acute listening taking place, not only to the sound but also to where it is coming from. It is natural to seek out the music of others in the hope of finding something that matches ones own vision, but as close as Martin Hayes’ way is to what I would wish, it is not quite mine. What my way is I cannot really put my finger on, but it is as if it is there waiting, and as time passes I have clearer and clearer intimations of it.

Here Martin Hayes speaks about his ‘first lesson’ from Tommie Potts: https://youtu.be/ljg-24c5Qr0. Tommie Potts was, as Michael O’Sullivan puts it ‘the epitome of tradition on the one hand, and…of innovation on the other’ Quoting O’Sullivan further:

‘Tommie was a deeply spiritual person. He would drop his voice and quote the lines of Scripture (Isaiah 64) “Eye hath not seen, nor ear heard…” and wide-eyed he would repeat the words “nor ear heard” for what he described as “the unbroken music of heaven”. Every time he lifted his fiddle it became an extension of a deep personal cry towards a rehearsal of that heavenly sound beyond and above consciousness – “ a music that you never would have known to listen for” (Seamus Heaney in ‘The Rain Stick’)’.

It is said that after retiring alone with his fiddle at night for several hours, traces of tears would be found on the floor where he had been playing (Seamus Ennis, sleeve notes to ‘Liffey Banks’).

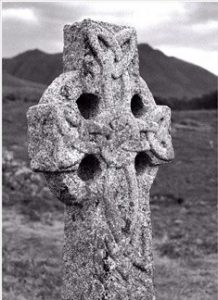

It has been a real journey of discovery for me, listening to the way that different musicians interpret the same tunes, and discerning where, according to my understanding, real quality and true feeling lies. It is to be found in the playing of relatively few individuals from amongst those playing today and those from the past. A final example of such playing comes from Joe Ryan in the last years of his life: https://youtu.be/ocxmdYGU9bk. The second tune, ‘Garden of Daisies’, expresses particularly well the sense of continuity I have referred to and which is perhaps also demonstrated by ancient Celtic knot designs:

Ashley West