Sinners is a 2025 American genre-fluid film drawing on the horror form of storytelling, written, co-produced, and directed by Ryan Coogler. The Swedish composer Ludwig Göransson composed the score. This is the fifth film both he and Coogler have collaborated in producing. Michael B. Jordan plays the leading part in dual roles as the identical twin brothers Elijah “Smoke” and Elias “Stack”, their names an apparent tribute to the blues singer Howlin’ Wolf’s Smokestack Lightning. The song was based on earlier blues songs and most likely first performed by Wolf (Chester Arthur Burnett) in the early 1930s. The central cast are made up by Wunmi Mosaku (Annie), Li Jun Li (Grace), Yao (Bo Chow), Miles Caton (Sammie), Delroy Lindo (Delta Slim), Hailee Steinfeld (Mary), Jack O’Connell (Remmick), Pearline (Jayme Lawson), Omar Benson Miller (Cornbread), David Maldonado (Hogwood). There is some fine cinematography by Autumn Cheyenne Durald Arkapaw who also worked alongside Ryan Coogler in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever and is also known for Last Showgirl.

The film is set in the Mississippi Delta during the Jim Crow era, as the twin brothers return to their hometown to set up their own business, a juke joint, an informal establishment featuring music, dancing, gambling, and drinking. The brothers have travelled the world and are military veterans of World War I. In the town the twins draw attention to themselves by Smoke’s wounding of two poor thieves who were preparing to steal some supplies from their truck, and by both showing, while paying over the odds for items they need and for hiring staff, that they have wads of cash. The money has come from some years living in Chicago working for, among others, Al Capone and stealing from gangsters, while playing the ‘mob’, both Irish and Italian, off against each other. What happens when the mob finds out is a question raised later in the film. Using their stolen money, they purchase a disused sawmill from a racist landowner Hogwood (David Maldonado), warning him when the transaction is done not to cross a line into what is now their property.

However, it is their younger cousin ‘Preacher Boy’ Sammie (played by Miles Caton) who ultimately attracts an unearthly supernatural danger. Sammie is the son of a preacher, a sharecropper and a gifted blues singer—his father Jedediah (Saul Williams) is a pastor who wants him to give up the guitar and live what he deems a virtuous life, but Sammie, who is drawn to the voice and music of the blues, has other ambitions. His father warns him the blues is devilish music, and if you dance with the devil sooner or later he will follow you home.

The Spirit of the Blues is central to and permeates the film. The character of Sammie is in part homage to the legendary Robert Johnson, ‘the King of the Delta Blues’. In his youth Johnson desperately wanted to be among the greatest of musicians and as he felt he didn’t come anywhere near to fulfilling this lofty ambition, the story has it, he met the Devil at a crossroads where he offered his soul in exchange for his subsequent extraordinary talent. Johnson became a masterful musician, and his striking legacy of 29 songs recorded in one year, influenced many including Bob Dylan, Muddy Waters, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards. In his final recording session in June 1937 he sang “Me and the Devil Blues” which tells the story of a singer waking up to the devil knocking on the door, telling him ‘it’s time to go”. His life was cloaked in mystery, his youthful death at the age of 27, along with the content of the songs he wrote, added to the lore of his alleged deal.

Sinners opens with a voiceover of history and mythopoeia of how some musicians, dating back to the West African Griots, the Irish Filidh, the Choctaw Firekeepers could cross to the ‘other side’ and become conduits between this world and one beyond. “There are legends of people with the gift of making music so true it can conjure spirits from the past and the future. The gift can bring fame and fortune but it also can pierce the veil between life and death.” Such piercing of the veil can stir forces best left be, allowing malevolent entities to enter the earthly world.

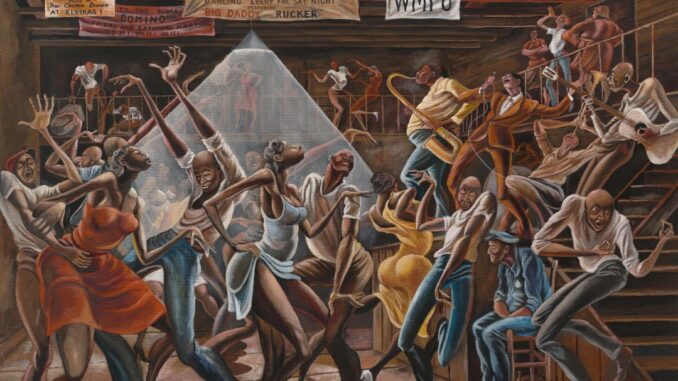

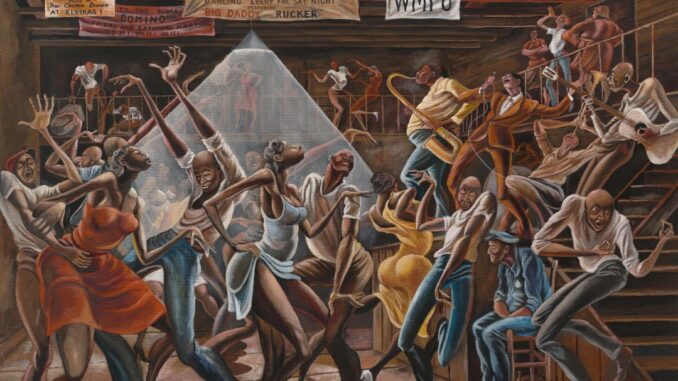

Shortly after the voice over fades an exhausted Sammie arrives in an automobile from which he exits and slowly walks into his father’s church, he tightly holds the neck of a shattered guitar in his right hand, his face is deeply scarred. His father calls on him to give up the music and the lifestyle that goes with it but the son refuses. The film then moves back twenty-four hours as the sun rises over cotton fields. Sammie comes running from working in the fields and after a token wash goes to talk with his father, informing him he is going to play music at the juke joint. Meanwhile the twin brothers purchase a barn and set about gathering musicians, catering services, and a security doorman so they can open their speakeasy that night. It comes to pass that by sundown the venue is ready a band is playing a blues number, here is revelry and dancing so presented as to evoke The Sugar Shack a 1976 painting by Ernie Barnes (1938 – 2009) which portrays the vibrant energy of Black American culture in the 20th century.

Although there are hints of what is to come in the opening scene and by the killing of a rattlesnake by the brothers, evil does not come directly into view until the arrival of Remmick (Jack O’Connell) who appears to drop down with a sizzling thud from the sky. With smoke emanating from his body he approaches an isolated shack where he cajoles the occupying couple Joan (Lola Kirke) and Bert (Peter Dreimanis) to invite him to enter. Remmick, a vampire, is closely pursued by indigenous hunters – they know the threat he poses and want to destroy him. They warn the couple of real impending danger but they do not listen to their concerns. As the sun is about to set, the Indians, knowing the power of the vampire is magnified with the onset of darkness, depart.

That night at the speakeasy Sammie performs a song with such a transcendent quality it summons spirits both from the past and future, shamanic apparitions, traditional African tribal dancers performing such unique dances as the Zaouli fuse with the crowd. As the dreamlike sequence of time transcending images continues the building appears to ignite into fire.

It is the music of Sammie that attracts the attention of Remmick. He wants him above all others, to turn him into a vampire and use his musical talents to reconnect to his own Irish ancestors. Remmick, who is centuries old, approaches the barn with Joan and Bert who he has already turned (into vampires). He seeks to be invited in, for neither he nor his cohorts can gain entry without first being invited to do so. After a telling exchange with the twins, they are refused entrance and bide their time outside playing their own music. Gradually their numbers grow, their singing culminating in a primitive circle dance with Remmick in its centre dancing a wild jig while he sings The Rocky Road to Dublin, a song carrying within it a defiant spirit of resilience against oppression and opposition. With this scene as in others, Coogler takes a risk: O’Connell is no great dancer yet his steps (through dint of sustained practice throughout the film’s making) helps to propel his satanic role, adding to the fire as the film shapes into its horror siege reminiscent of George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968).

This is not a typical vampire film. It uses the genre to relate an allegorical tale using vampire horror images as narrative tools. In an interview with USA Today Coolger explained that the movie was about “identity” which encapsulates ancestors and place. Who are black, who are white, why was it so in the era the film is set, for a black man to gaze momentarily at a white woman could cost him his life. In a time when blacks could be murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan and as was stated by the character Frank Bailey (Michael Rooker) in the 1988 film Mississippi Burning, “and there ain’t a court in Mississippi that’d convict me for it.” This atmospheric tension can be viewed within the context of the film when Mary a white woman who had a relationship with Stack some years before wishes to enter the speakeasy. To allow her in could draw down the KKK, however as she has black ancestry codes of conduct may be wavered.

The vampires in Sinners are not cast in the mold of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. After being turned they do not entirely lose their human qualities, they affirm family, togetherness, eternal happiness but at the cost of what the brothers seek most, freedom. In the film the Christian cosmology is not affirmed, it is portrayed as being colonial, imposed and oppressive. It is the pagan spirituality strikingly portrayed by the spiritualist Annie (Wunmi Mosaku) who practices Hoodoo, a form of African American folk medicine and magic, that is shown to be powerful and life affirming. Annie, when she first appears in the film, is the estranged wife of Smoke with whom she had a child. She is shown to be wise, knows most about the vampires and how to overcome them. She is a protector not only of the brothers but also of all who come within the orbit of her mothering care.

Remmick desperately wishes to connect to his ancestors, he hates those who came and stole their land and imposed a new religion, a religion he despises, but the picture he offers is not clear cut. When he has Sammy in his clutches and Sammy begins to recite the Lord’s prayer, Remmick joins in, declaring it gives him comfort. Remmick warns the twins and those not yet turned they have been lied to, declaring, “I am your way out, this world has already left you dead.” He tells terrible truths laced with comforting lies. Salvation, which many seek, has many shades and, as Meister Eckhart indicated, there is the dark side of God.

There is much hidden in the film revealing itself upon closer examination, not least the relationship between the Irish and Black America. In his incisive book How The Irish Became White Noel Ignatiev recalls how for a brief period the Irish, who were called “Niggers turned inside out”, and Blacks “Smoked Irish” stood together, but there are more than one ‘vampirish’ ways of turning. The Irish were turned, to climb up society’s ladder they needed to be seen to be White – White Americans as proffered by the likes of the KKK. And what of Black America? Would it have been better off staying separate as advocated by Malcolm X and several within the Black Panther movement, to return to their own ancestry rather beggaring for acceptance in a land where they were brought as manacled slaves? Slaves were property and had monetary value to their owner. The dispossessed Irish, especially after the implementation of the Penal Laws (introduced in 1695), were as nothing, without value. Both peoples were viewed as being closer to apes than to Homo sapiens. They were simple minded, ignorant, not to be trusted, needing to be kept in their place.

Before he is destroyed Remmick reveals he has done a deal with the KKK, an organisation he wishes eventually to eliminate. The barn was from the outset an ambush. When, at the film’s end, Klan members return to finish what the vampires have begun, Smoke is waiting for them.

The subtle and symbolic differences between the brothers are also played out, when they first appear on screen Smoke wears a blue scalley cap, Stack wears a red fedora hat, the colours and style have their own significance as do their names Elijah and Elias. Playing the roles of identical twins (even with the guidance of twins Noah and Logan Miller) was no mean feat and it required a second viewing of the film to note how well Jordan had studied for and played his role. The intimacy between Smoke and Stack is of two siblings who were so close that nothing could come between them, this is not about Cain killing Abel, but of his killing of Adam.

There is a good deal of history touched upon in the film, not least acknowledgement is offered to the place of the Chinese and how hard they worked and suffered to try and live the ‘American dream’. However, it also has its shortcomings, among which are its portrayal of Christianity as a powerless and conservative religion. The Southern Black Church played a strong role in trying to protect the oppressed and vulnerable. It provided solace when there was little or no State or Federal protection. Despite many of its members being lynched and numerous Church burnings it maintained its voice, helped to sustain the community and played a critical role in the march for civil rights. Aspects of Remmick are also somewhat vague. Which religion does he reject, was it the one brought to Ireland in the 5th Century or modifications to that religion which came centuries later? It is also left somewhat vague as to which ancestors he wishes to reconnect with, for in truth “the Irish whoever they may have been have long since departed this earth – what is left are but remnants.”

Sinners features two end-credit scenes, one appears in the middle while a shorter one appears at the very end. The middle scene takes place in 1992 when Sammie is an old blues singer. After a soulful performance, he receives a revealing visit from Stack and Mary. Stack makes Sammie an offer that he refuses staying with the life that called him to the music of the blues, a music which he can still play pure. Stack doesn’t persuade any further, but both acknowledge that the fateful day was the best of their life, with Stack stating it was the last time he saw the sun, saw his brother and briefly felt free. The touching brief post-credit scene shows Sammie singing alone This Little Light of Mine as a younger man in the church.

____________________

I was drawn to view this film mainly because of my interest in the Blues. Its sound first entered me when I heard Muddy Waters (McKinley Morganfield 1913-1983) playing in an old library hall in December 1970. His style of music has been described as “raining down Delta beatitude” whether or not this be true I do not know, and though the sound that night was electrified and not to the liking of those who wanted the music pure, I remember the ‘rhythm of ease’ in the bands play and the laid back-back of Muddy Waters humming through the cords.

Ted McNamara