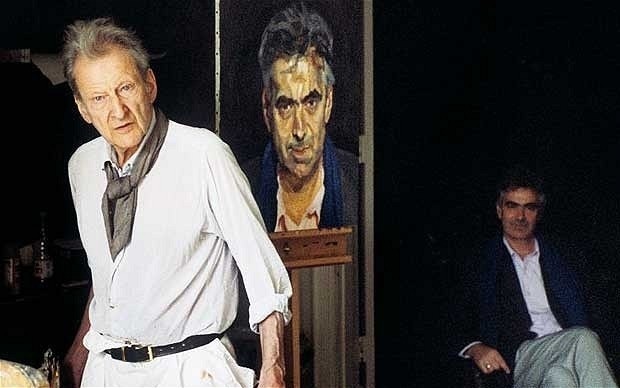

Lucian Freud and ‘Man with a Blue Scarf’, a portrait of Martin Gayford

Can one really receive the presence of another person? This question is with me at the moment.

I visited the exhibition of Lucian Freud’s work at the National Portrait Gallery and found that afterwards, in a quiet moment, one picture in particular appeared in my mind’s eye and touched my feelings. In it a head emerges, slightly lowered, from a dark background, and the dark eyes have an arresting look. It gives the impression of a certain intensity, a current of accord between artist and sitter.

How to convey the truth, the reality of another person? It is a question Lucian Freud was evidently exploring in the long hours he demanded of his sitters and significantly it is this, one of his most direct and least mannered portraits, that came back to me.I had been struck more by the being of the person portrayed than by the brilliant application of paint.

This led me to reflect that ordinarily there is so much in oneself that prevents one from seeing, let alone really receiving, another person. One very large canvas in the show seems to illustrate this. The foreground is entirely filled with a magnificent house plant, each blade of the leaves very realistically rendered with their bitingly sharp edges. In the background, far behind and to the left is a small portrait of the artist’s head, reflected in a mirror, his hand to his ear as if listening with difficulty. What a visual allegory for all that stands in the way of meeting and connecting with another person!

Interior With Plant, Reflection Listening. 1967-8

Perhaps a particular inner state is needed in order really to attend to another person. Recently I came across a passage in a novel conveying just such an experience. In ‘The Cat’s Table ‘ by Michael Ondaatje we get a very entertaining (in some respects autobiographical?) tale in which three eleven year old boys, unaccompanied minors, are let loose in the liner which is carrying them from Ceylon, as it was then, to boarding school in England. As a teenager, the author/narrator spent holiday time in London with the family of one of the boys, his friend Ramadhin. Some years later he is summoned unexpectedly to Ramadhin’s funeral and afterwards the author describes how in a moment of quietness and grief, Ramadhin “came right into my heart and I started crying. Everything about him was suddenly there in me: his slow stroll, his awkwardness around a questionable joke…how his body looked when he walked away from you.” The times they spent together were vividly recalled, how they had become close without fully realising it. The shock of death can be the catalyst for such an experience.

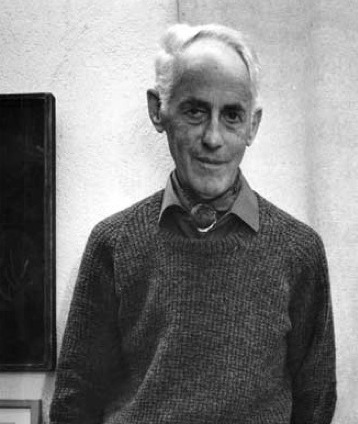

As an undergraduate at Cambridge in the early ‘60s I was among the students who sometimes visited Kettles Yard where Jim Ede held open house in the afternoons. He would show us round his collection of art and objects accumulated over a lifetime, particularly in the ’30s when he had been an assistant at the Tate and close friends with artists in the St. Ives group. Guided round the house by him and looking at the way things were arranged in relation to each other, we absorbed something of Jim’s acute visual awareness, the foundation of an artistic education. If we lingered, engaged in conversation, we might be invited to tea in the long dining alcove which reminded me of a monastery refectory. There was wholemeal bread which his wife, Helen, would say was,’from that crank shop in Rose Crescent’, the marmalade was brought out of the fridge, and a fine teapot was set upon the wooden table….

It was many, many years later that I revisited Kettles Yard: Jim had since moved to Edinburgh and had died, but as I sat downstairs in his simple monk-like cell of a bedroom, I was filled with a sense of his presence, his presence in a fuller sense than I seemed ever to have encountered in his lifetime. I met him, his living spirit in a wholly new way.

I have often visited Kettles Yard since, enjoying the simple beauty of the place, and certain pictures and sculptures that have become like friends, but I know I will not be privileged to encounter Jim, himself, in the same way again, though an appreciation of him can still be invoked.

Lesley Croome

Photos of Jim Ede (above)and of an interior at Kettles Yard by William Smalley

References:

Lucian Freud Portraits were at the National Portrait Gallery London in May 2012

Man with a Blue Scarf-On Sitting for a Portrait by Lucian Freud by Martin Gayford

The Cat’s Table. A novel by Michael Ondaatje

Kettle’s Yard: http://www.kettlesyard.co.uk/